Image generated using artificial intelligence for illustrative purposes. The irony is not lost.

A simple question at an air show

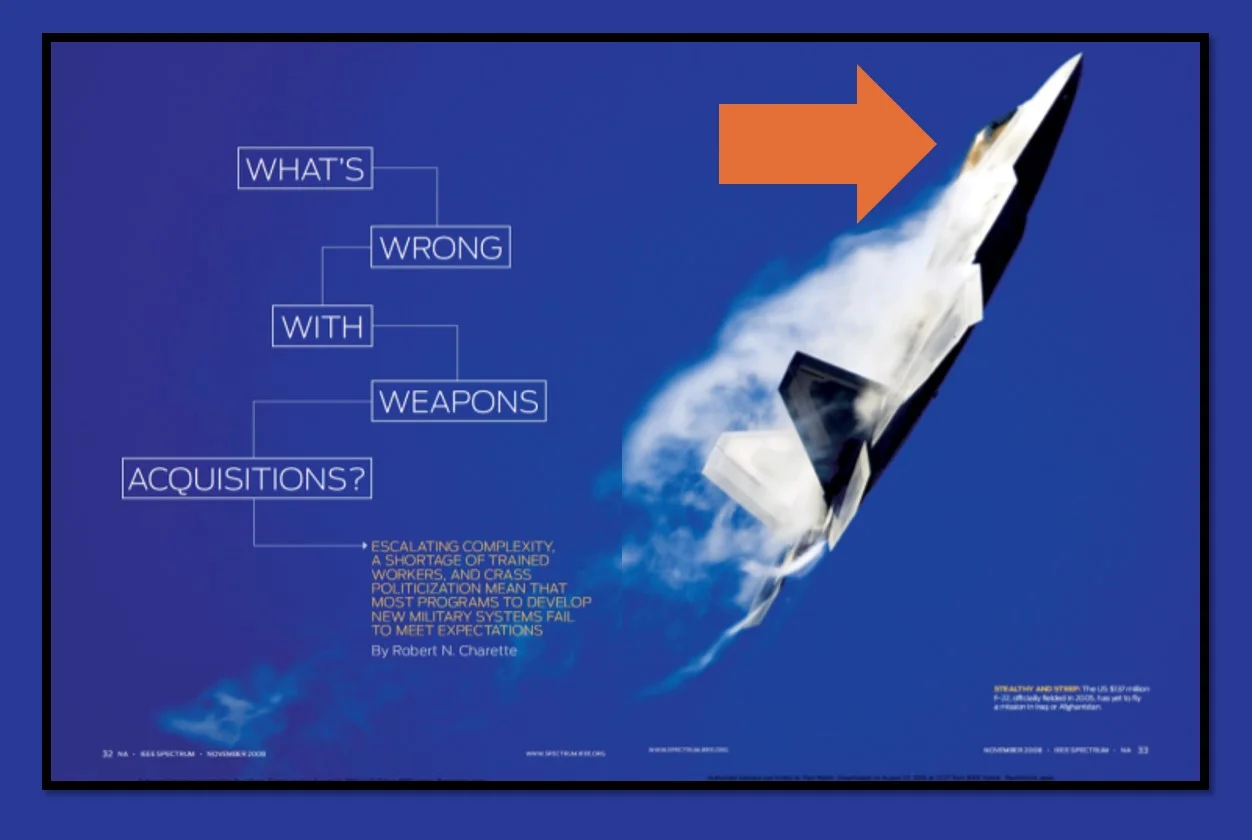

About thirty years ago, I took my wife and our six kids to an air show. Like most people, we were drawn to the most striking aircraft on the flight line: a stealth fighter. The pilot was standing nearby, proudly showing off his aircraft. And it was his aircraft; his name was stenciled on the side of the jet.

The pilot was used to getting questions that dealt with speed, maneuverability, and mission capability. But as a budding systems engineer at the time, I started to view systems through a life-cycle framework. So, I asked something completely different.

“Is this thing hard to maintain?”

He paused, rolled his eyes, and said, “You have no idea.”

That response stayed with me. The aircraft clearly met its operational objectives, but only by accepting extraordinary sustainment complexity. Performance was optimized, and supportability paid the price. That was not a Systems Engineering failure; it was a deliberate trade-off.

To me, the lesson was clear: No matter how advanced a system becomes, it does not escape the life cycle. It simply shifts where cost, risk, and operational friction will appear.

(USAF Photo) U.S. Air Force airmen shut down an F-117 Nighthawk following its farewell flyover ceremony at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base on March 11, 2008, ahead of the aircraft’s retirement later that year.

Enter the Singularity narrative

Fast-forward to today, and discussions of artificial intelligence increasingly invoke the concept of the Singularity. The term was popularized by Ray Kurzweil, who described it as a period in which technological change becomes so rapid and profound that human life is irreversibly transformed [1].

It is important to note that the Singularity is not a universally accepted framework within AI research. Many practitioners reject it as speculative or overly metaphorical [2]. Nevertheless, it has become influential in public discourse and policy-related conversations and therefore warrants examination through a systems engineering lens.

In popular narratives, the Singularity is often associated with systems that:

Improve themselves autonomously

Scale with minimal marginal cost

Recover from faults without human intervention

Reduce or eliminate human cognitive limitations

Human-machine merging, including concepts such as mind uploading, is sometimes presented as a logical endpoint of this progression [3]. The emphasis is overwhelmingly on capability and acceleration.*

What is largely absent from these discussions is sustained attention to the later stages of the system life cycle.

The missing conversation: support and disposal

Systems engineers are trained to ask questions that are uncomfortable precisely because they are unavoidable [5]:

How will this system be maintained over time?

Who provides that support, under what constraints, and at what cost?

How does the system fail, degrade, or drift from its intended configuration?

What does retirement, decommissioning, or disposal actually entail?

When these questions are applied to software-intensive or AI-enabled systems, they become even more challenging. When applied to systems that blur the boundary between tool and actor, they become foundational.

If cognition is augmented, migrated, or replicated, what exactly is being supported? A biological substrate, a digital substrate, or an evolving combination of both? If multiple instantiations exist, which one is authoritative? If state and memory are backed up, who governs their retention, restoration, or deletion?

Disposal in this context is not merely a technical concern. It is ethical, legal, and societal [6]. Yet Singularity narratives often treat these issues as secondary, assuming they will be resolved by future innovation or emergent norms.

History suggests otherwise.

Sustainment debt scales with ambition

The stealth fighter pilot’s response illustrates a broader principle: advanced capability does not eliminate sustainment burden. It concentrates and amplifies it.

Stealth platforms required specialized materials, controlled environments, intensive inspection regimes, and extensive maintenance hours per flight hour [7]. Over time, sustainment dominated life-cycle cost and operational availability. The system succeeded operationally, but only through continuous, resource-intensive support.

Now scale that lesson to AI-enabled systems that:

Operate continuously rather than episodically

Adapt autonomously rather than through managed upgrades

Interact with other agents rather than static interfaces

Accumulate state, memory, and learned behavior over time

In such systems, support becomes a first-order design driver. Configuration management is no longer administrative; it is existential [5]. Disposal is not an afterthought; it is a defining requirement.

A long-lived, high-consequence system that cannot be safely supported or responsibly decommissioned is incomplete, regardless of how impressive its performance may be.

A systems engineering reframing of the Singularity

From a systems engineering perspective, the Singularity is not a destination. It is a stress test.

It tests whether we can:

Maintain control and accountability as systems grow more complex

Govern systems that evolve faster than organizational and regulatory structures

Define explicit end-of-life criteria for systems whose functionality and identity may change over time

A system passes this test not by exceeding human capability, but by remaining controllable, supportable, and terminable under defined conditions [3].

Ignoring support and disposal does not make these problems disappear. It defers them until they are more expensive, more hazardous, and more difficult to reverse.

The enduring value of life-cycle thinking

That moment at the air show was a reminder that good engineering is not dazzled by performance alone. It is grounded in realism and accountability.

Even optimistic assessments of AI correctly note that automation and learning systems may reduce certain support burdens. They do not eliminate the need for governance, configuration control, or end-of-life decisions [4,6]. Every system, no matter how intelligent or adaptive, remains embedded in a larger socio-technical environment.

As discussions of AI acceleration and human-machine integration continue, systems engineers play a critical role. Not as futurists or alarmists, but as practitioners trained to think across the full life cycle.

The future may reward capability. It will be shaped by support. And it will be judged by how responsible disposal is handled.

Reflection for practitioners

If the Singularity represents a new class of systems, then systems engineering must respond by sharpening, not abandoning, its core questions. The question I asked that pilot at the airshow decades ago still stands:

Who will maintain this, at what cost, and what happens when its time is over?

* Author’s note: I have previously examined the risks of overextended metaphors in technological discourse. See my 2012 blog, “When Models and Metaphors Are Dangerous.”

Optional Reader Resource

References

Kurzweil, Ray. The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology. Viking, 2005.

Russell, Stuart. Human Compatible: Artificial Intelligence and the Problem of Control. Viking, 2019.

Kurzweil, Ray. The Singularity Is Nearer: When We Merge with AI. Viking, 2024;

INCOSE. Systems Engineering Handbook: A Guide for System Life Cycle Processes and Activities. 5th ed., Wiley, 2023.

Floridi, Luciano. The Ethics of Artificial Intelligence: Principles, Challenges, and Opportunities. Oxford UP, 2019.

U.S. Government Accountability Office. F-35 Joint Strike Fighter: Development Is Nearly Complete, but Deficiencies Found in Testing Need to Be Resolved. GAO-18-321, Apr. 2018; U.S. Air Force Scientific Advisory Board. Sustainment and Logistics Challenges for Low Observable Aircraft. U.S. Air Force, 2017.