[Conceptual illustration of space-based computing infrastructure communicating via inter-satellite links. Image generated using an AI image generation tool (OpenAI), for illustrative purposes only.]

Servers in Space and Architectural Alternatives

Considering Fundamentally Different Architectures Through a Systems Engineering Lens

In recent discussions about the future of computing infrastructure, Elon Musk has floated the idea of placing “servers in space.”[1] Stripped of its headline appeal, this idea presents systems engineers with something far more familiar than it first appears: a proposal for a fundamentally different system architecture intended to satisfy largely the same stakeholder needs as today’s terrestrial server farms.

This is not a new pattern. In fact, it is a textbook illustration of a long-standing Systems Engineering principle. The INCOSE Systems Engineering Handbook has consistently emphasized that good architecture work requires the deliberate exploration of alternatives that differ meaningfully in how they meet stakeholder requirements, rather than converging too early on a single solution.

Handbook Guidance, Then and Now

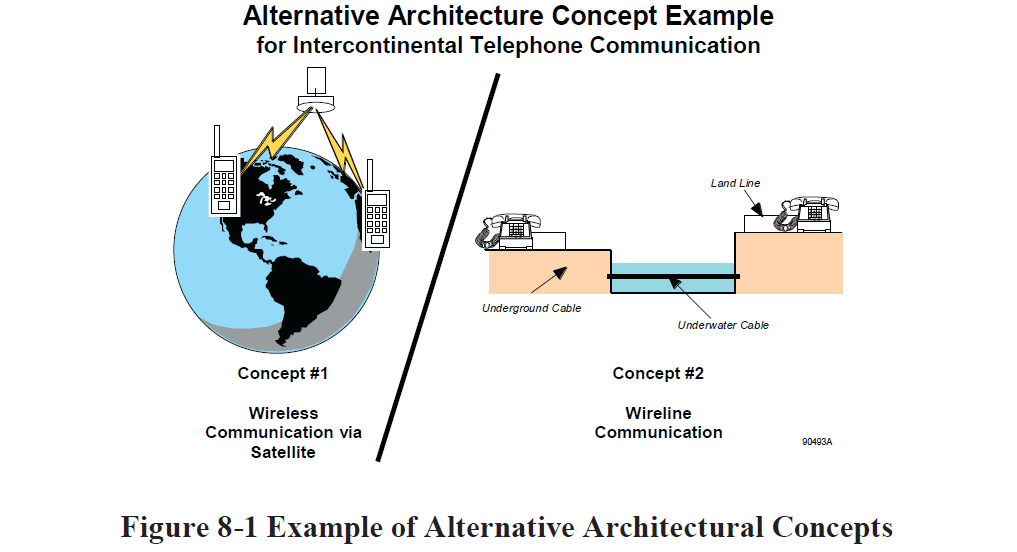

The 2007 Version 3.1 of the INCOSE Systems Engineering Handbook captured this principle succinctly: systems engineers should consider developing architectural alternatives that are significantly different in their approach to meeting stakeholder requirements. Figure 8-1 in that edition illustrated this idea using intercontinental telephone communication, contrasting wireless satellite-based communication with wireline communication via underground and underwater cables. Both architectures served the same mission, but they did so through entirely different technical and operational means [2].

Figure taken from International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE), Systems Engineering Handbook, Version 3.1, INCOSE-TP-2003-002-03.1, 2007

While the wording has evolved, the intent remains intact in the current Version 5.0 Handbook. Within the System Architecture Definition process, practitioners are directed to develop and evaluate alternative architectural solutions that satisfy system requirements while addressing constraints, life-cycle considerations, and stakeholder concerns [3]. The emphasis is not on refining a single concept, but on exploring a trade space that includes genuinely distinct architectural approaches before selection and refinement.

The sentiment is unchanged: architecture decisions are strongest when they emerge from comparison, not assumption.

Applying the Principle to Modern Computing Infrastructure

Viewed through this lens, the comparison between terrestrial server farms and space-based computing infrastructure aligns cleanly with the Handbook’s guidance on architectural alternatives.

Concept 1: Terrestrial Server Infrastructure

Terrestrial server farms represent the dominant architectural solution for large-scale computing today. Computer resources are centralized or regionally distributed on Earth, supported by power grids, cooling systems, fiber-optic networks, and physical access for maintenance and upgrades. This architecture operates within well-understood regulatory, environmental, and operational constraints. It favors accessibility, incremental scaling, and frequent hardware refresh cycles.

From a systems perspective, this concept embeds assumptions about proximity to users, reliance on terrestrial energy and communications infrastructure, and the feasibility of hands-on operations. These assumptions are rarely questioned precisely because the architecture is mature and familiar.

However, even within this terrestrial concept, there is a wide range of environmental alternatives that shape system behavior and trade-offs. Hyperscale providers have intentionally sited data centers in cooler climates to reduce cooling loads, such as facilities in Scandinavia, while others operate underground in repurposed mines and hardened subterranean facilities to improve thermal stability and physical security. Additional deployments in rural or agricultural regions leverage land availability and proximity to renewable energy sources, particularly wind and solar, to address power and sustainability constraints. These within-domain variations illustrate how architectural thinking adapts to environmental constraints while remaining terrestrial, and they provide a natural transition point for considering whether remaining challenges are best addressed through further optimization on Earth or through a shift to an entirely different operational domain [4][5][6].

Concept 2: Space-Based Computing Infrastructure

Placing servers in space represents a radically different architectural approach to meeting similar stakeholder needs such as global availability, performance, and scalability. In this concept, computer resources are deployed in orbit, powered primarily by solar energy, and integrated with space-based communication networks. Operations are constrained by launch opportunities, mass and volume limits, radiation exposure, and limited opportunities for physical intervention.

This architecture replaces terrestrial constraints with space-domain constraints. Maintenance strategies shift toward autonomy and redundancy. Scaling becomes tied to launch cadence rather than data center construction. Regulatory oversight expands into orbital management and spectrum coordination. Whether advantageous or not, these differences are precisely what make the concept architecturally valuable to explore.

The Systems Engineering Value of Comparing Architectural Alternatives

The value of examining “servers in space” does not lie in predicting whether such systems will be deployed at scale. Its value lies in reinforcing a core Systems Engineering discipline: architecture selection must be informed by the deliberate comparison of alternatives that challenge baseline assumptions.

The Handbook’s guidance, across its many versions, is clear that architecture definition is not an exercise in novelty or optimization alone. It is a structured decision process that benefits from considering options that differ in operating domain, life-cycle strategy, and constraint sets. Often, the outcome of this process is the rejection of a bold alternative, but that rejection is informed rather than reflexive.

Final Thought

The enduring lesson from both the Handbook and the “servers in space” discussion is that good Systems Engineering demands architectural imagination tempered by disciplined analysis. By placing fundamentally different concepts side by side, systems engineers expose hidden assumptions, clarify stakeholder priorities, and strengthen the rationale for the architecture ultimately selected.

Whether computing remains firmly on Earth or someday expands into orbit is secondary. What matters is preserving the practice of considering architectures that are meaningfully different before deciding which one best serves the system’s mission.

Optional Reader Resource

References

Driebusch, Corrie, et al. "Why Elon Musk Is Racing to Take SpaceX Public." The Wall Street Journal, 21 Jan. 2026, www.wsj.com/tech/why-elon-musk-is-racing-to-take-spacex-public-38f3de9b

International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE), Systems Engineering Handbook, Version 3.1, INCOSE-TP-2003-002-03.1, 2007

International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE), Systems Engineering Handbook: A Guide for System Life Cycle Processes and Activities, Version 5.0, Wiley, 2023. https://www.incose.org/resources-publications/technical-publications/se-handbook/

Google, “Data Centers: Efficiency and Location Strategy,” Google Sustainability, 2019. https://datacenters.google/operating-sustainably/

Meta Platforms, Inc., “Our Global Data Center Infrastructure,” Meta Data Centers, 2020. https://datacenters.atmeta.com/

"Inside 'The Underground'." Iron Mountain, 2 Nov. 2025, https://www.ironmountain.com/data-centers/about/news-and-events/news/2024/december/data-centers-inside-the-underground-iron-mountain-in-butler-county Accessed 31 Jan. 2026.