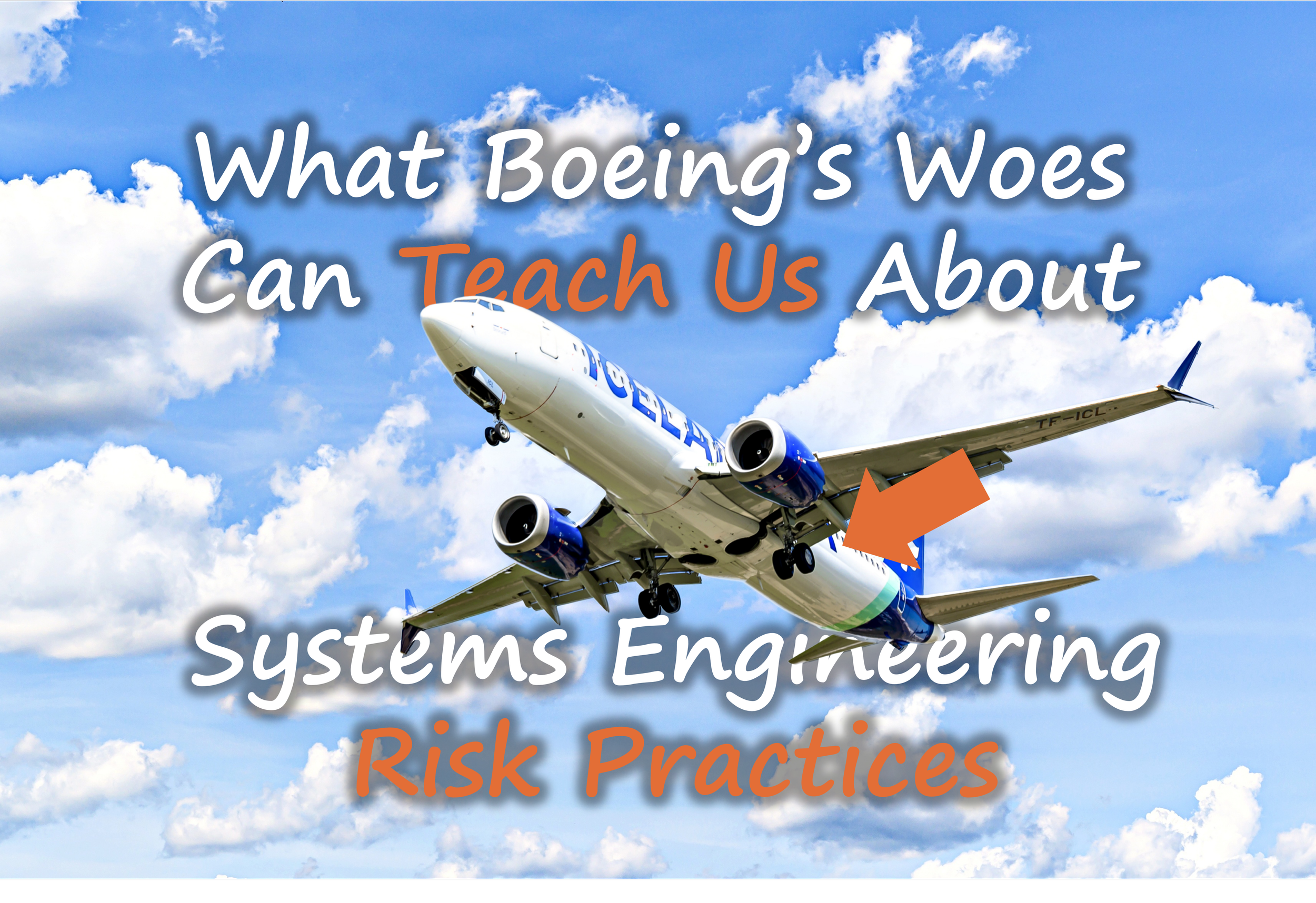

A Troubling Time for Boeing

In early 2024, a Boeing 737‑9 MAX experienced a mid‑cabin door plug blowout shortly after takeoff, forcing an emergency landing and grounding of aircraft across multiple airlines. [4, 11] This incident followed years of heightened scrutiny stemming from the 737 MAX crashes and continuing concerns about manufacturing quality on the 787 Dreamliner production line. [2, 13]

For systems engineers, Boeing’s situation is not merely an aviation headline. It is a high‑visibility reminder that even mature organizations with decades of engineering success can experience systemic risk failures when risk management practices erode or become disconnected from day‑to‑day decision making.

This raises a critical question: How do well‑established engineering organizations still experience cascading, enterprise‑level risk failures?

The Nature of Risk in Complex Sociotechnical Systems

Boeing operates as a classic system‑of‑systems, in which aircraft development and production involve tightly coupled technical systems, a global supplier network, regulatory oversight, workforce skills, corporate governance, and persistent schedule and cost pressures. [8]

From a systems engineering perspective, risk in such environments extends well beyond technical performance parameters. In addition to hardware and software risks, programs must actively manage organizational, process, supplier, and cultural risks. Research in safety‑critical industries consistently shows that these non‑technical risks often act as amplifiers, turning localized issues into systemic failures. [12, 10]

INCOSE defines risk as the effect of uncertainty on objectives. In Boeing’s case, uncertainties related to manufacturing variability, workforce experience, supplier quality, and management decision‑making directly affected safety, quality, schedule, cost, and public trust.[8]

Why Did Boeing’s Risk Practices Stop Working?

Incomplete Risk Identification

Multiple investigations and media reports indicate that recurring manufacturing nonconformances and process breakdowns were not isolated surprises. Internal audits, employee reports, and whistleblower disclosures raised concerns about production practices and inspection rigor well before major incidents occurred. [14, 1]

However, these signals were not consistently elevated or treated as enterprise‑level risks. Over time, organizations can fall into a pattern of normalization of deviance, where known issues are accepted as manageable because they have not yet resulted in catastrophic outcomes. [15]

When risk identification focuses primarily on technical design while discounting process discipline and workforce conditions, critical hazards remain invisible at the program level.

Weak Risk Analysis and Prioritization

Even when risks are identified, they must be analyzed and prioritized relative to competing pressures. In Boeing’s case, safety‑critical risks appear to have competed directly with aggressive production schedules, cost targets, and delivery commitments [6].

Risk analysis that underestimates cascading effects—such as how a small manufacturing lapse can propagate through integration, operations, and certification—creates blind spots. Systems engineering literature emphasizes that leading indicators, such as rework trends, training gaps, and supplier defect rates, are essential for detecting emerging risk before operational failure occurs [8, 10].

Without disciplined prioritization, high‑impact, low‑probability risks are often deferred until they manifest operationally.

Ineffective Risk Mitigation and Controls

Risk mitigation is only effective if controls are consistently implemented and verified. Investigations following the 737‑9 MAX incident identified breakdowns in documented work instructions, inspection steps, and verification of completed tasks. [5, 11]

In a distributed supplier environment, inconsistent enforcement of process controls significantly weakens risk mitigation strategies. Risk acceptance decisions, whether explicit or implicit, must be documented, justified, and escalated appropriately. When risk acceptance becomes routine rather than exceptional, individual risks begin to accumulate, often crossing program and organizational boundaries and collectively exceeding the organization’s defined risk tolerance without any single decision appearing unacceptable in isolation. [9]

Organizational Culture as a Risk Factor

Culture plays a decisive role in whether risk management succeeds or fails. Reports surrounding Boeing frequently highlight tension between engineering judgment and management pressure, particularly where schedule and financial objectives dominate decision‑making. [6, 7]

When engineers do not feel empowered to stop production, elevate concerns, or challenge assumptions, psychological safety erodes. Over time, this undermines the very feedback mechanisms that effective risk management depends upon. [3]

A strong risk culture treats bad news as valuable data—not as an obstacle to delivery.

Mapping Boeing’s Challenges to INCOSE Risk Management Practices

INCOSE positions Risk Management as a continuous, lifecycle‑spanning technical management process. Effective risk management interfaces closely with technical planning, decision analysis, quality assurance, and configuration management. [8]

Boeing’s challenges illustrate what happens when these interfaces weaken. Risk becomes siloed, reactive, and disconnected from daily engineering and production decisions.

Tailoring risk practices to system complexity and criticality is essential; however, tailoring should not eliminate fundamental risk management activities or controls. Tailoring must preserve hazard identification, risk analysis, mitigation, monitoring, and escalation mechanisms regardless of program context. [8]

Lessons Learned for Practicing Systems Engineers

Boeing’s experience offers several important lessons for systems engineers across all industries. Large‑scale engineering failures rarely stem from a single error; instead, they emerge when small risks accumulate unchecked across technical, organizational, and cultural boundaries.

Key takeaways for practicing systems engineers include:

Treat organizational culture, suppliers, and process discipline as legitimate and ongoing risk sources

Use leading indicators (e.g., rework trends, training gaps, supplier performance) in addition to lagging performance metrics

Escalate, document, and periodically revisit risk acceptance decisions, particularly when risks aggregate across program boundaries

Strengthen interfaces between risk management, configuration management, and quality assurance

Risk management is not paperwork—it is an active control mechanism for complex systems. Disciplined, integrated risk practices are foundational to safety, trust, and long‑term system resilience.

Where might similar risks be quietly accumulating in your program today?

Optional Reader Resource

Download: SE Risk Management Checklist (INCOSE‑Aligned)

A practical checklist to help systems engineers assess whether risk practices are truly integrated across planning, design, suppliers, and operations.

References

Associated Press. (2024, January 6). Boeing faces new questions about the 737 Max after a plane suffers a gaping hole in its side. https://apnews.com/article/79bc1ea98ee7fbc6edf46aff9319775b

Department of Justice. (2021, January 7). Boeing charged with 737 Max fraud conspiracy and agrees to pay over $2.5 billion. https://www.justice.gov/archives/opa/pr/boeing-charged-737-max-fraud-conspiracy-and-agrees-pay-over-25-billion

Edmondson, A. (2018). The fearless organization: Creating psychological safety in the workplace for learning, innovation, and growth. Wiley.

Federal Aviation Administration. (2024, January 6). Updates on Boeing 737-9 MAX aircraft. https://www.faa.gov/newsroom/updates-boeing-737-9-max-aircraft

Federal Aviation Administration. (2024, January 12). FAA increasing oversight of Boeing production and manufacturing. https://www.faa.gov/newsroom/faa-increasing-oversight-boeing-production-and-manufacturing

Gelles, D., & Kitroeff, N. (2019). Flying blind: The 737 MAX tragedy and the fall of Boeing. Doubleday.

Harvard Business School. (2020). Why Boeing’s problems with the 737 MAX began more than 25 years ago. https://www.library.hbs.edu/working-knowledge/why-boeings-problems-with-737-max-began-more-than-25-years-ago

International Council on Systems Engineering. (2023). INCOSE systems engineering handbook (5th ed.). Wiley.

International Organization for Standardization. (2018). ISO 31000: Risk management — Guidelines. https://www.iso.org/standard/65694.html

Leveson, N. (2011). Engineering a safer world: Systems thinking applied to safety. MIT Press.

National Transportation Safety Board. (2024). Investigative update: Alaska Airlines Flight 1282, Boeing 737-9 MAX. https://www.ntsb.gov/investigations/Pages/DCA24MA063.aspx

Reason, J. (1997). Managing the risks of organizational accidents. Ashgate.

Reuters. (2024, June 13). Boeing investigates quality problem on undelivered 787s, sources say. https://www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/boeing-investigates-quality-problem-undelivered-787s-sources-say-2024-06-13/

(This article may be behind a paywall.)

Reuters. (2024, March 4). US FAA hits Boeing 737 MAX production for quality control issues. https://www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/us-faa-says-boeing-737-max-production-audit-found-compliance-issues-2024-03-04/ (This article may be behind a paywall.)

Vaughan, D. (1996). The Challenger launch decision: Risky technology, culture, and deviance at NASA. University of Chicago Press.